Breaking News

Valley Between Tigris And Euphrates

воскресенье 12 апреля admin 94

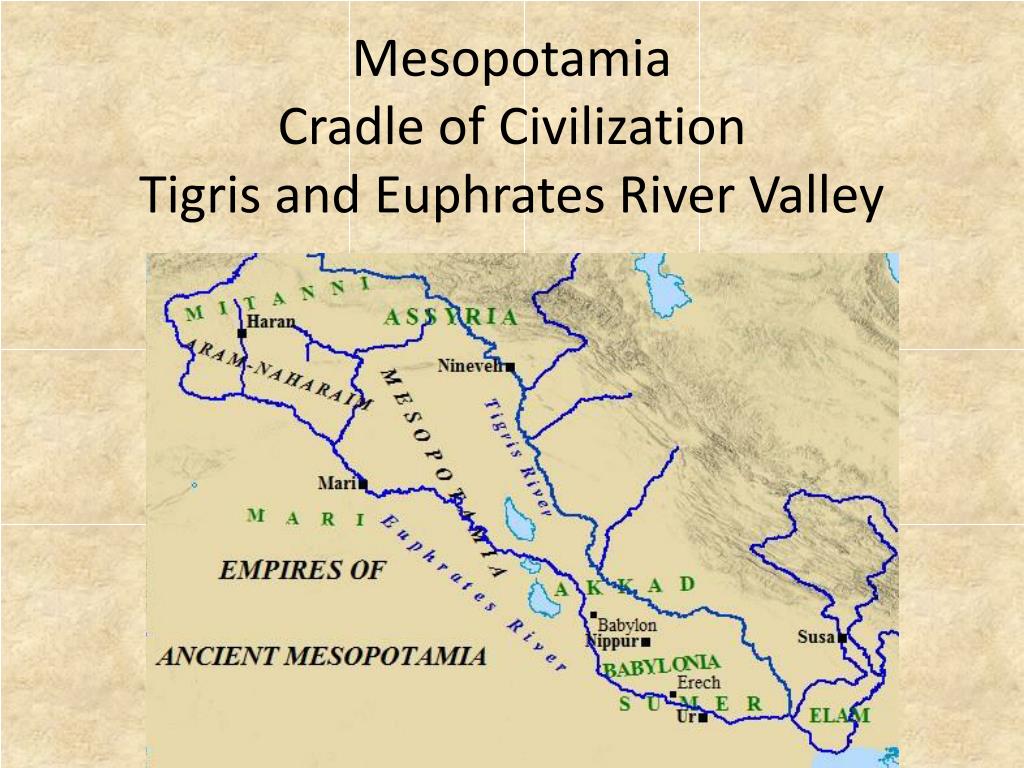

Egypt (The Nile River Valley). Mesopotamia means “the land between two rivers. What is the area between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers called? Mesopotamia is Greek for 'between the rivers.' Specifically, the rivers referenced by this term are the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that run through modern-day Iraq. These two rivers, and the land between them, are often called the 'cradle of civilization' because the civilization that developed there was likely the first ever on Earth.

| Tigris–Euphrates river system | |

|---|---|

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Palearctic |

| Biome | Flooded grasslands and savannas |

| Geography | |

| Area | 35,600 km2 (13,700 sq mi) |

| Countries | Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait[1][2][3][4] |

| Oceans or seas | None |

| Rivers | Tigris, Euphrates, Greater Zab, Lesser Zab. |

| Climate type | Subtropical, hot and arid |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Critical/endangered[citation needed] |

The Tigris and Euphrates, with their tributaries, form a major river system in Western Asia. From sources originating in Eastern Anatolia, they flow by/through Syria through Iraq into the Persian Gulf.[5] The system is part of the Palearctic Tigris–Euphrates ecoregion, which includes Iraq and parts of Turkey, Syria, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Jordan.

From their sources and upper courses in the mountains of eastern Turkey, the rivers descend through valleys and gorges to the uplands of Syria and northern Iraq and then to the alluvial plain of central Iraq. The rivers flow in a south-easterly direction through the central plain and combine at Al-Qurnah to form the Shatt al-Arab and discharge into the Persian Gulf.[6]

The region has historical importance as part of the Fertile Crescent region, in which civilization is believed to have first emerged.

Geography[edit]

The ecoregion is characterized by two large rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates. The rivers have several small tributaries which feed into the system from shallow freshwater lakes, swamps, and marshes, all surrounded by desert. The hydrology of these vast marshes is extremely important to the ecology of the entire upper Persian Gulf. Historically, the area is known as Mesopotamia. As part of the larger Fertile Crescent, it saw the earliest emergence of literate urban civilization in the Uruk period, for which reason it is often described as a 'Cradle of Civilization'.

In the 1980s, this ecoregion was put in grave danger as the Iran–Iraq War raged within its boundaries. The wetlands of Iraq, which were inhabited by the Marsh Arabs, were almost completely dried out, and have only recently[when?] shown signs of recovery.

The Tigris–Euphrates Basin is shared by Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran and Kuwait.[4] Many Tigris tributaries originate in Iran and a Tigris–Euphrates confluence forms part of the Kuwait–Iraq border.[7] Since the 1960s and in the 1970s, when Turkey began the GAP project in earnest, water disputes have regularly occurred in addition to the associated dam's effects on the environment. In addition, Syrian and Iranian dam construction has also contributed to political tension within the basin, particularly during drought.

General description[edit]

The general climate of the region is subtropical, hot and arid. At the northern end of the Persian Gulf is the vast floodplain of the Euphrates, Tigris, and Karun Rivers, featuring huge permanent lakes, marshes, and forest. The aquatic vegetation includes reeds, rushes, and papyrus, which support numerous species. Areas around the Tigris and the Euphrates are very fertile. Marshy land is home to water birds, some stopping here while migrating, and some spending the winter in these marshes living off the lizards, snakes, frogs, and fish. Other animals found in these marshes are water buffalo, two endemicrodent species, antelopes and gazelles and small animals such as the jerboa and several other mammals.

Ecological threats[edit]

Iraq suffers from desertification and soil salination due in large part to thousands of years of agricultural activity. Water and plant life are sparse. Saddam Hussein's government water-control projects drained the inhabited marsh areas east of An Nasiriyah by drying up or diverting streams and rivers. Shi'a Muslims were displaced under the Ba'athist regime. The destruction of the natural habitat poses serious threats to the area's wildlife populations. There are also inadequate supplies of potable water.

The marshlands were an extensive natural wetlands ecosystem which developed over thousands of years in the Tigris–Euphrates basin and once covered 15–20,000 square kilometers. According to the United Nations Environmental Program and the AMAR Charitable Foundation, between 84% and 90% of the marshes have been destroyed since the 1970s. In 1994, 60 percent of the wetlands were destroyed by Hussein's regime – drained to permit military access and greater political control of the native Marsh Arabs. Canals, dykes and dams were built routing the water of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers around the marshes, instead of allowing water to move slowly through the marshland. After part of the Euphrates was dried up due to re-routing its water to the sea, a dam was built so water could not back up from the Tigris and sustain the former marshland. Some marshlands were burned and pipes buried underground helped to carry away water for quicker drying.

The drying of the marshes led to the disappearance of the salt-tolerant vegetation; the plankton rich waters that fertilized surrounding soils; 52 native fish species; the wild boar, red fox, buffalo and water birds of the marsh habitat.

Water dispute[edit]

The issue of water rights became a point of contention for Iraq, Turkey and Syria beginning in the 1960s when Turkey implemented a public-works project (the GAP project) aimed at harvesting the water from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers through the construction of 22 dams, for irrigation and hydroelectric energy purposes. Although the water dispute between Turkey and Syria was more problematic, the GAP project was also perceived as a threat by Iraq. The tension between Turkey and Iraq about the issue was increased by the effect of Syria and Turkey's participation in the UN embargo against Iraq following the Gulf War. However, the issue had never become as significant as the water dispute between Turkey and Syria.[8]

The 2008 drought in Iraq sparked new negotiations between Iraq and Turkey over trans-boundary river flows. Although the drought affected Turkey, Syria and Iran as well, Iraq complained regularly about reduced water flows. Iraq particularly complained about the Euphrates River because of the large amount of dams on the river. Turkey agreed to increase the flow several times, beyond its means in order to supply Iraq with extra water. Iraq has seen significant declines in water storage and crop yields because of the drought. To make matters worse, Iraq's water infrastructure has suffered from years of conflict and neglect.[9]

In 2008, Turkey, Iraq and Syria agreed to restart the Joint Trilateral Committee on water for the three nations for better water resources management. Turkey, Iraq and Syria signed a memorandum of understanding on September 3, 2009, in order to strengthen communication within the Tigris–Euphrates Basin and to develop joint water-flow-monitoring stations. On September 19, 2009, Turkey formally agreed to increase the flow of the Euphrates River to 450 to 500 m³/s, but only until October 20, 2009. In exchange, Iraq agreed to trade petroleum with Turkey and help curb Kurdish militant activity in their border region. One of Turkey's last large GAP dams on the Tigris – the Ilisu Dam – is strongly opposed by Iraq and is the source of political strife.[10]

Conservation[edit]

The Mesopotamian Marshes in southern Iraq were historically the largest wetland ecosystem of Western Eurasia. Their drainage began in the 1950s, to reclaim land for agriculture and oil exploration. Saddam Hussein extended this work in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as part of ecological warfare against the Marsh Arabs, a rebellious group of people in Baathist Iraq. However, with the breaching of the dikes by local communities after the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the ending of a four-year drought that same year, the process has been reversed and the marshes have experienced a substantial rate of recovery. The permanent wetlands now cover more than 50% of pre-1970s levels, with a remarkable regrowth of the Hammar and Hawizeh Marshes and some recovery of the Central Marshes.[11]

- Conservation status: critical/endangered

- Protected area

- Endemic species: Basra reed warbler (Acrocephalus griseldis), Iraq babbler (Turdoides altirostris)

- Threatened species: Basra reed warbler (Acrocephalus griseldis) - endangered

- Possibly extinct species: Bunn's short-tailed bandicoot rat (Nesokia bunnii)

In media[edit]

- Dawn of the World, film, 2008.

- Zaman, The Man From The Reeds, film, 2003

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Matthew Zentner (2012). Design and impact of water treaties: Managing climate change. p. 144.

The Tigris-Euphrates-Shatt al Arab is shared between Iraq, Iran, Syria, Kuwait and Turkey.

- ^'Lower Tigris & Euphrates'. feow.org. 2013.

- ^'Mesopotamia (2/3/2003)'.

- ^ abDeniz Bozkurt; Omer Lutfi Sen (2012). 'Hydrological response of past and future climate changes in the Euphrates-Tigris Basin'(PDF). p. 1.

The Euphrates-Tigris Basin, covering areas in five countries (Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Kuwait), is a major water resource of the Middle East.

- ^Gibson, McGuire (17 March 2014). 'Tigris-Euphrates river system'. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^'Euphrates River'. Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^Dan Caldwel (2011). Vortex of Conflict: U.S. Policy Toward Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. p. 60.

- ^Uzgel I., 1992. GÜVENSİZLİK ÜÇGENİ: TÜRKİYE, SURİYE, IRAK VE SU SORUNU, MÜLKİYELİLER BİRLİĞİ DERGİSİ, 162, p.47-52

- ^https://www.reuters.com/article/environmentNews/idUSTRE54M0XG20090523 Turkey lets more water out of dams to Iraq: MP

- ^https://web.archive.org/web/20101231233038/http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5giDgd3ukLR8UcfziUQcNToKyM_tw Turkey to up Euphrates flow to Iraq

- ^Iraqi Marshlands: Steady Progress to RecoveryArchived 2011-06-08 at the Wayback Machine (UNEP)

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tigris–Euphrates river system |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mesopotamia (Middle East). |

| Amur meadow steppe | China, Russia |

| Bohai Sea saline meadow | China |

| Nenjiang River grassland | China |

| Nile Delta flooded savanna | Egypt |

| Saharan halophytics | Algeria, Egypt, Mauritania, Tunisia, Western Sahara |

| Tigris–Euphrates alluvial salt marsh | Iraq, Iran |

| Ussuri-Wusuli meadow and forest meadow | China, Russia |

| Yellow Sea saline meadow | China |

A river valley civilization or river culture is an agricultural nation or civilization situated beside and drawing sustenance from a river. A 'civilization' means a society with large permanent settlements featuring urban development, social satisfaction, specialization of labor, centralized organization, and written or other formal means of communication. A river gives the inhabitants a reliable source of water for drinking and agriculture. Additional benefits include fishing, fertile soil due to annual flooding, and ease of transportation. The first great civilizations, such as those in Mesopotamia and Egypt, all grew up in river valleys.

History of the above civilizations[edit]

Civilization first began about 3500 BC[citation needed], along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the Middle East; the name given to that civilization, Mesopotamia, means 'between rivers'. The Nile valley in Egypt had been home to agricultural settlements as early as 5500 BC, but the growth of Egypt as a civilization began around 3100 BC[citation needed]. Zuma online gratis. A third civilization grew up along the Indus River around 2600 BC, in parts of what is now India and Pakistan. The fourth great river civilization emerged around 1700 BC along the Yellow River in China.[1][2]

Civilizations tended to grow up in river valleys for a number of reasons. The most obvious is access to a usually reliable source of water for agriculture and other needs. Plentiful water and the enrichment of the soil due to annual floods made it possible to grow excess crops beyond what was needed to sustain an agricultural village. This allowed for some members of the community to engage in non-agricultural activities such as the construction of buildings and cities (the root of the word 'civilization'), metalworking, trade, and social organization.[3][4] Boats on the river provided an easy and efficient way to transport people and goods, allowing for the development of trade and facilitating central control of outlying areas.[5]

Early civilizations[edit]

Fertile Crescent[edit]

Mesopotamia[edit]

Mesopotamia was the earliest river valley civilization, starting to form around 3500 BC. The civilization was created after regular trading started relationships between multiple cities and states around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Mesopotamian cities became self-run civil governments. One of the cities within this civilization, Ur, was the first literate society in history. Eventually, they constructed irrigation systems to exploit the two rivers, transforming their dry land into an agriculturally productive area, allowing population growth throughout the cities and states within Mesopotamia.[6]

Egypt[edit]

Egypt also created irrigation systems from its local river, the Nile River, more complex than previous systems. The Egyptians would rotate legumes with cereal which would stop salt buildup from the freshwater[clarification needed] and enhance the fertility of their fields. The Nile River also allowed easier travel, eventually resulting in the creation of two kingdoms in the north and south areas of the river until both were unified into one society by 3000 BC.[7]

Indus valley[edit]

Much of the history of the Indus valley civilization is unknown. Discovered in the 1920s, Harappan society remains a mystery because the Harappan system of writing has not yet been deciphered. It was larger than either Egypt or Mesopotamia. Historians have found no evidence of violence or a ruling class; there are no distinctive burial sites and there is not a lot of evidence to suggest a formal military. However, historians believe that the lack of knowledge about the ruling class and the military is mainly due to the inability to read Harappan writing.[8]

Yellow River[edit]

The Yellow River (Huang He) area became settled. Many tribes settled along the river, ninth longest in the world, which was distinguished by its heavy load of yellow silt and its periodic devastating floods. A major impetus for the tribes to unite into a single kingdom by around 1500 BCE was the desire to find a solution to the frequent deadly floods. The Yellow River is often called 'The Cradle of Chinese Civilization'.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^McCannon, John (2008). Barron's AP World History. Barron's Educational Series Inc. pp. 57–60. ISBN978-0-7641-3822-5.

- ^'The River Valley Civilization Guide'. rivervalleycivilizations.com. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^Rivers and Civilization: What's the Link?. Mindsparks. 2007. p. 8. ISBN978-1-57596-251-1.

- ^Mountjoy, Shane (2005). Rivers in World History: The Indus River. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 15.

- ^'Indus River Valley Civilization'. The River Valley Civilization Guide. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^Adrian Cole and Stephen Ortega, The Thinking Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 83, 95-101.

- ^Adrian Cole and Stephen Ortega, The Thinking Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 83, 95-101.

- ^Adrian Cole and Stephen Ortega, The Thinking Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 106-108.

Further reading[edit]

- Clayton, Peter A. & Dent, John (1973). The Ancient River Civilizations: Western Man & the Modern World. Elsevier. ISBN9780080172095